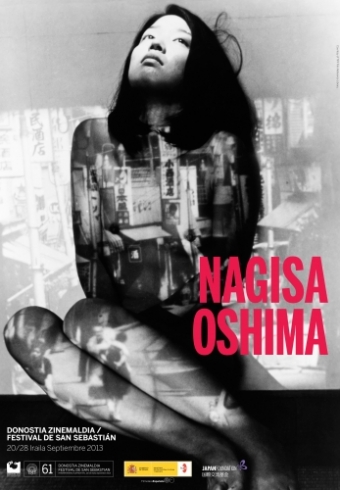

A retrospective will be dedicated to the Japanese moviemaker Nagisa Oshima at the 61st San Sebastian Festival, to run from 20-28 September 2013.

Nagisa Oshima (Okayama, 1932) is not only one of Japanese cinema´s most remarkable moviemakers; he is also one of its most audacious, controversial and contentious figures. An iconic director of the so-called nuberu bagu (new wave) in the 60s, in subsequent decades he went on to become one of Japanese cinema’s best known names at international level. Oshima made his movie debut in 1959 with Aito Kibo no Machi / Street of Love and Hope, an early approach to the problem of youths and his first work for the Shochiku studio, one of the biggest in Japan. This was followed by other works with Shochiku, by that time clearly defining his critical style and angry view of Japanese society: Seishun Zankoku Monogatari / Cruel Story of Youth (1960) and Taiyô no Hakaba / The Sun´s Burial (1960). However, his next film, Nihon no Yoru to Kiri / Night and Fog in Japan (1960), is an overtly political film after which Oshima left the studio to become an independent producer.

That second period in Oshima´s filmography was an enormously creative time when he made a series of films portraying his obsessions with and reflections on sex, politics, violence and death, always used as tools to analyse the ulcers of his time. His formal solutions, greatly inspired by the European “new waves” and avant-garde theatre techniques, made him one of the most representative filmmakers of Japanese modernity, thanks to titles including Shiiku / The Catch (1961), Etsuraku (Pleasures of the Flesh, 1964), Muri Shinju: Nihon no natsu / Japanese Summer: Double Suicide (1967), Kôshikei / Death by Hanging (1968), Shinjuku dorobo nikki / Diary of a Shinjuku Thief (1968), Shonen (Boy, 1969) and Gishiki / The Ceremony (1971).

The year 1976 saw Oshima gain international renown for Ai no korîda (In the Realm of the Senses). Although the film caused a worldwide scandal for its explicit portrayal of sexuality and earned the wrath of censors in Japan, it was presented in the Directors´ Fortnight at the Festival de Cannes and went on to become the best known work of his career. He was therefore able to film a co-production with France, another sincere work on the power of desire Ai no borei (Empire of Passion, 1978), for which he won the Best Director Award at the Festival de Cannes. He subsequently shot two European co-productions of wide international repercussion: the war film Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence (1983) and the disturbing Max mon amour (1986), both of which represent his new approach to sexual desire as a destabilising element of the social network. His last film for the big screen, Gohatto (Gohatto: Taboo, 2000), is yet another unusual work that openly tackles the matter of homosexuality among the samurais. In 1988 he took part of the Official Jury of the San Sebastian Film Festival.

The retrospective programmed by the San Sebastian Festival includes all of Oshima´s films for the big screen. In addition to demonstrating the evolution of his career, the initiative will include several titles never seen before in Spain. The cycle, jointly rganised with the Filmoteca Española and the collaboration of The Japan Foundation, will be accompanied by a book coordinated by Quim Casas.

FILMS IN THE CYCLE

Aito Kibo no Machi / Street of Love and Hope (AKA A Town of Love and Hope) 1959

In his first work Oshima already demonstrates his interest in the people abandoned in the wake of Japan´s “economic miracle” seen through the story of Masao, a young boy with no choice but to support his sick mother and mentally-ill sister.

Seishun Zankoku Monogatari / Cruel Story of Youth (aka Naked Youth) 1960

A powerful generational portrait of two “angry” Japanese youngsters in the 60 built around the stormy relationship between the unscrupulous Kiyoshi and the pretty Makoto, who helps him to blackmail the older men who make sexual propositions to her.

Taiyô no Hakaba / The Sun's Burial 1960

A chronicle of life in the dregs of the Osaka underworld, a claustrophobic social frieze revolving around a prostitute who runs a sordid business: trafficking in the blood of people who are obliged to sell it to survive.

Nihon no Yoru to Kiri / Night and Fog in Japan 1960

Oshima´s first obviously political film describes the tension in the ranks of the Zinkyoto, the left-wing Japanese student movement. A work of surprising visual style reflecting the ideological disillusionment of an entire generation.

Shiiku / The Catch 1961

Adaptation of a novel by Kenzaburo Oé set in World War II: an Afro-American pilot is captured by the inhabitants of a small village. The situation is used by Oshima to depict yet another unrelenting X-ray of Japanese society.

Amakusa shiro tokisada / Shiro Amakusa, the Christian Rebel (aka The revolutionary) 1962

Inroads by Oshima to historic films through the tale of Christian rebel Shiro Amakusa, who led the peasants´ campaign against the Shogunate in the 17th century. The director draws on the past to construct a metaphor on the present and the political repressions of the 60s.

Etsuraku (Pleasures of the Flesh, 1964)

A thriller-like film, asphyxiating and melancholy, where a man who has committed a murder is blackmailed by another who witnessed the crime. A journey through the labyrinths of prostitution and pornography, hosted by the Yakuza.

Hakuchû no tôrima / Violence at Noon 1966

A new study by Oshima of the sexuality and violence that mark Japanese society: the portrayal of a rapist and killer of women constructed thanks to the memories of his wife and one of his victims. One of the director’s most tense and astounding works.

Nihon shunka-kô / Sing a Song of Sex (aka A Treatise on Japanese Bawdy Songs) 1967

Oshima follows the odyssey of four college students obsessed by sex and obscene songs. A tragicomic fantasy, delirious and grotesque, on his recurring themes: repressed desire and the complex relations between sexes.

Muri Shinju: Nihon no natsu / Japanese Summer: Double Suicide (aka Night of the Killer) 1967

The Japanese tradition of shinju (or the double suicide of two lovers) is taken up again by Oshima in one of his most enigmatic works. The artistic vanguards of the period join hands in a fatalistic, tragic film of refined aesthetics.

Ninja bugei-Chô / Tales of the Ninja (aka Band of Ninja) 1967

A surprising contribution by Oshima to animation cinema taking a popular manga by Sampei Shirato to the screen. An experimental work depicting a completely different way of understanding animated film.

Kaette kita yopparai / Three Resurrected Drunkards (aka Sinner in paradise) 1968

A courageous denunciation of the xenophobia congenital to Japanese society: three students go on holiday to a coastal village, where they are mistaken for Koreans, an ethnic minority particularly unpopular with the locals.

Shinjuku dorobo nikki / Diary of a Shinjuku Thief 1968

The adventures of a book thief in the Japanese district of Shinjuku give the basis to a film-collage taking its inspiration from experimental theatre and analysing the secret connection between sexuality and political activism.

Kôshikei / Death by Hanging 1968

A dark satire following the Kafkaesque ups and downs of a Korean man condemned to death who survives hanging. Based on a true story, the film demonstrates the extent to which Oshima cleverly drew on the teachings of modern European cinema.

Shonen (Boy, 1969)

A sordid true story once again provides Oshima with inspiration for one of his most direct and striking discourses on social corruption: a boy is repeatedly used by his parents as a false traffic accident victim so that they can claim compensation.

Tokyo senso sengo hiwa / The Man Who Left His Will on Film (aka He Died after the War) 1970

An independent production shot by Oshima with non-professional actors, in complete underground film spirit and aesthetics akin to the documentary. An audacious testimony of the Japanese counterculture of the time.

Gishiki / The Ceremony, 1971

The most venerated Japanese traditions are laid bare in this sharp satire using a wedding ceremony to highlight the tensions underlying social facades.

Natsu no imôto (Dear Summer Sister, 1972)

Set on Okinawa Island, a bittersweet tale of how a young generation is obliged to live with the undercurrent of a traumatic past: World War II and the Japanese occupation.

Ai no koriida (The Realm of the Senses, 1976)

The film for which Oshima earned worldwide fame and marked a new era in the way sexuality was portrayed in cinema. The true story of Sada Abe, the woman who killed and castrated her lover, became in Oshima’s hands an out-and-out declaration of principles on the subversive power of sex.

Ai no borei (Empire of Passion, 1978)

Oshima takes the tradition of kaidan-eiga (ghost stories), so widespread in Japanese cinema, to construct this beautiful film on a passionate and tragic love affair that defies social taboos.

Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence (1982)

An international co-production on which Oshima worked with big-name stars like David Bowie, Ryuichi Sakamoto and Takeshi Kitano. What at first seems to be a traditional war film turns into yet another of the director’s explorations of the chasms of desire.

Max mon amour (1986)

Oshima takes another step forward in his constant quest to test the limits and taboos that condition sexual relations. Charlotte Rampling plays a married, middle-class woman who has an affair with a rather surprising lover: a chimpanzee.

Gohatto (Gohatto: Taboo, 2000)

In his last film Oshima proposes a synthesis of the subjects to have obsessed him throughout his filmography. Here samurai cinema is portrayed from a very unusual angle: homosexual relations in its closed world.

Classic retrospective

A regular chapter in the Festival retrospective section has been a cycle dedicated to a classic director, enabling us to appreciate the little or virtually unknown work of such filmmakers as Robert Siodmak, James Whale, William Dieterle, William A. Wellman, Gregory La Cava, Tod Browning, Mitchell Leisen, Mikio Naruse, John M. Stahl, Carol Reed, Frank Borzage, Michael Powell, Preston Sturges, Anthony Mann, Robert Wise, Ernst Lubitsch, Henry King, Mario Monicelli, Richard Brooks, Don Siegel, Jacques Demy and George Franju.