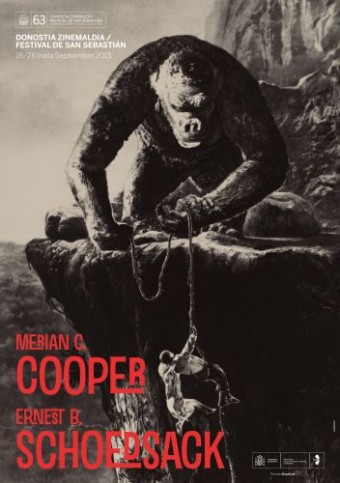

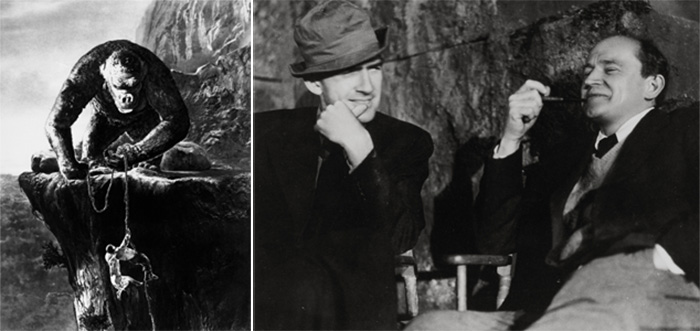

Merian C. Cooper (1893-1973) and Ernest B. Schoedsack (1893-1979) were, in the golden age of North American movies, one of the strangest and most exciting creative twosomes ever to come out of Hollywood. This year’s edition of the San Sebastian Festival will recover their work in a cycle dedicated to their films as directors.

Acclaimed for generations as the masterminds of the iconic King Kong (1933), Cooper and Schoedsack’s contribution to fantasy cinema didn’t stop at this chef d’oeuvre remodelling the Beauty and the Beast myth, instead creating a delirious and antediluvian visual world taking its inspiration from Gustave Doré and innovating the stop motion animation technique. They also brought us other equally attractive proposals with titles such as The Most Dangerous Game (1932), the fabulous movie about man hunting man, produced by Cooper and directed by Schoedsack and Irving Pichel, and Dr. Cyclops (1940), a telluric fantasy about miniature beings helmed solo by Schoedsack.

Cooper was a fighter pilot in the First World War, a POW in a German camp, a member of a volunteer squadron during the subsequent conflict between Poland and the Soviet Union, and later again a colonel in the US Army Air Forces during World War II. Schoedsack too fought in the first battle, but as a member of the Signal Corps, the army information squad. He produced many works as a journalist and took his first steps in the movie industry as a cameraman at Mack Sennett’s Keystone Pictures. Both born adventurers, they participated in several anthropological expeditions as cameramen, hence their passion for documentary cinema.

They made their debut jointly directing two masterpieces in the genre, Grass (1925) and Chang (1927). In the former they portrayed the everyday lives of a nomad tribe in Persia (today’s Iran), while in the latter they focussed on the relationship between a native from the Siam jungle and a baby elephant. Although they later made fantasy, drama, adventure and whodunnit movies, their fictional films always smacked of strong throwback to their documentary apprenticeship: the tales of King Kong and Zaroff suggest contact with exotic unexplored worlds as bigger-than-life fantasy merges throughout their work with the realities of the jungles and mountains of Asia and Africa. Hence the enormously personal style that characterises their films. After their first two documentaries they made The Four Feathers (1929), the first talkie version of A.E.W. Masson’s famous book about honour and cowardice.

The Cooper-Schoedsack combo forged full steam ahead throughout the 30s, forming a team with the screenwriter Ruth Rose (1891-1978). Rose and Schoedsack had coincided on an expedition to the Galapagos Island and married in 1926. The three launched films in difference genres, produced by Cooper and helmed solo or in collaboration by Schoedsack: mystery films like The Monkey's Paw (1933) and Blind Adventure (1933); adventure stories such as Trouble in Morocco (1937) and Outlaws of the Orient (1937); an adaptation of Bulwer-Lytton’s popular novel The Last Days of Pompeii (1935); and even comedy-dramas like Long Lost Father (1934), starring John Barrymore. Of their hugely successful King Kong, which would go decades later to generate remakes shot by John Guillermin and Peter Jackson, they too made delightful continuations and offshoots: Son of Kong (1933) and Mighty Joe Young (1949). The stop motion style used by Willis O’Brien in the first Kong was repeated in Mighty Joe Young by Ray Harryhausen, who went on to become one of the great masters of this artisan procedure.

Following the enormous challenge of King Kong, heyday of the 30’s fantasy genre and metaphor of the economic situation assailing the country after the Wall Street crash of 1929, Cooper gradually distanced himself from directing and took up position as one of the leading producers at RKO. As studio head, he would produce, among other films, the first of the elegant musical comedies for Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, Flying Down to Rio (1933), by Thornton Freeland, and the adventure fantasy She (1935), by Lansing C. Holden and Irving Pichel, according to the novel by H. Rider Haggard, of which a remake was made years later, produced by Hammer Film.

In 1933 he joined forces with David O. Selznick at Pioneer Pictures, a production company dedicated to experimenting with trichrome Technicolor: the first film launched by Pioneer using the technique was Becky Sharp (1935), by Rouben Mamoulian. Later, towards the end of the forties, he founded with John Ford the small independent company Argosy Pictures, with which they produced The Fugitive (1947), Fort Apache (1948), Rio Grande (1950), The Quiet Man (1952) and The Searchers (1956), among other movies by Ford. Cooper was also among the promotors of the Cinerama format, created by the photographer and moviemaker Fred Waller, in the early 50s.

The retrospective, dedicated to their work as directors in addition to those made solo by Schoedsack, is organised by the San Sebastian Festival in collaboration with the Filmoteca Española. The cycle will be accompanied by the publication of a book dedicated to the two filmmakers.

Related news:

- 19/ 08/ 2015

The 63rd San Sebastian Festival will dedicate a retrospective to directors Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack

- 06/ 05/ 2015

Donostia Zinemaldiaren 63. edizioak atzera begirakoa eskainiko die Merian C. Cooper eta Ernest B. Schoedsack zuzendariei

We remind you that you can purchase books of the previous years retrospectives on the

Festival's Publications store .

A regular chapter in the Festival retrospective section has been a cycle dedicated to a classic director, enabling us to appreciate the little or virtually unknown work of such filmmakers as Robert Siodmak, James Whale, William Dieterle, William A. Wellman, Gregory La Cava, Tod Browning, Mitchell Leisen, Mikio Naruse, John M. Stahl, Carol Reed, Frank Borzage, Michael Powell, Preston Sturges, Anthony Mann, Robert Wise, Ernst Lubitsch, Henry King, Mario Monicelli, Richard Brooks, Don Siegel, Jacques Demy, George Franju and Dorothy Arzner.